1 Overview of HS2

2 Changing Justifications

3 Inconvenient Truths and Ignored Alternatives

1.0 Overview of HS2

High Speed 2 (HS2) is the Government’s proposed new ultra-high speed rail line.

The Government currently say HS2 will cost £55.7 billion to build. The costs originally started at £32.7bn in 2010 and were last updated in 2015, but despite the fact Government said the last increase was purely to account for inflation, an FOI request we submitted showed this was a lie. The National Audit Office stated in 2016 that HS2 Ltd were running £7bn over budget, a fact which was not contested by HS2 Ltd. This should put the official cost at £63bn.

Phase 1 would not run until 2026 at the earliest, with stations in just Birmingham and London. Phase 2 would have stations in Manchester, (near) Nottingham and Leeds but is currently due for completion in 2033. The proposed Sheffield station was recently cancelled, and whilst the Government state they intend to build a station near Crewe, the cost of this is not incorporated into the official estimates.

Whilst there were previous proposals to link HS2 to Heathrow Airport and the Channel Tunnel, these have both been shelved, with no reduction to the cost of the project.

YouGov polls show that opposition to HS2 greatly exceeds support: the latest poll for the Sunday Times in October 2014 found 54% of voters are opposed to HS2, with only 24% in favour. A survey for ITV in November 2016 found only 15% of the public thought HS2 would be worth the official cost of £56bn.

The 2011 Transport Select Committee inquiry into HS2 in 2011 concluded:

“Many issues about the Government’s proposal for HS2 and about high-speed rail in general have been raised in the course of our inquiry. We have pointed to a number of areas that we believe need to be addressed by the Government in the course of progressing HS2. These include the provision of greater clarity on the policy context, the assessment of alternatives, the financial and economic case, the environmental impacts, connections to Heathrow and the justification for the particular route being proposed.”

The case for HS2 has got significantly worse since 2011, alternatives have been repeatedly dismissed with the Department for Transport admitting that a high speed railway is worse for the environment than a conventional speed railway, the policy context now shows that the HS2 announcement just before the 2010 election was rushed through by the previous Labour Cabinet without proper scrutiny, with Peter Mandelson telling the Financial Times:

“In 2010, when the then Labour government decided to back HS2, we did so based on the best estimates of what it would involve. But these were almost entirely speculative. The decision was also partly politically driven. In addition to the projected cost, we gave insufficient attention to the massive disruption to many people’s lives construction would bring. We were focusing on the coming electoral battle, not on the detailed facts and figures of an investment that did not present us with any immediate spending choices.”

The reality was that the decision to proceed with HS2 was made in a policy vaccum, without any assessment of what was best for Britains transport infrastructure. Sir Rod Eddington warned the Department for Transport of what was happening when they commissioned him to produce a detailed report on transport policy. He said:

“It is critical that the government enforces a strong, strategic approach to option generation, so that it can avoid momentum building up behind particular solutions and the UK can avoid costly mistakes which will not be the most effective way of delivering on its strategic priorities.”

“The risk is that transport policy can become the pursuit of icons. Almost invariably such projects – ‘grands projets’ – develop real momentum, driven by strong lobbying. The momentum can make such projects difficult – and unpopular – to stop, even when the benefit/cost equation does not stack up, or the environmental and landscape impacts are unacceptable. The resources absorbed by such projects could often be much better used elsewhere.”

“The approach taken to the development of some very high-speed rail line options has been the opposite of the approach advocated in this study. That is, the challenge to be tackled has not been fully understood before a solution has been generated.”

2.0 Changing Justifications

Over time, Government and supporters of HS2 have cited a series of changing justifications as to why the ;project is not just needed, but ‘essential’. The main reason there have been so many justifications over the years is that the decision to proceed with HS2 was made without any real justification after strong lobbying from advocates in the construction industry. As such, the arguments to support HS2 were bolted on after the decision had already been made, which is why none of them fit or stand up to scrutiny.

2.1 We Are Being ‘Left Behind’

Possibly the weakest argument of all which has been used to justify the building of HS2 is that we invented the railways but are being ‘left behind’ by other countries which have been investing heavily in high speed rail networks, and that in the UK we only have 68 miles of high speed rail, namely HS1 in Kent.

This is simply not the case, as with the globally accepted definition of what qualifies as high speed rail being trains and tracks capable of 124mph, we have had high speed rail since the 1970s. In 2009, the House of Commons library stated that for the area of the country, we had the third most developed high speed rail network in the world, and more has been upgraded since then. Whilst former Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin was one of those HS2 advocates willing to say the UK has a minimal HSR network, despite being present for the opening ceremony of high speed services on the Midland Mainline in 2014.

2.2 HS2 – An Alternative to Flying

The original set of MPs who supported HS2 did so because they saw it as an alternative to building a third runway at Heathrow. Indeed, even though current Transport Secretary Chris Grayling says ‘The case for HS2 is a strong as ever’, when asked about airport expansion in 2009 he said:

“Actually, I was the person who – when I was Shadow Transport Secretary – first proposed our alternative policy; a high-speed rail line linking Leeds and Manchester to Birmingham, Heathrow, London, Paris and Brussels. That will take huge pressures off Heathrow.”

Of course, HS2 does not go to either Heathrow or the channel tunnel, and modal shift figures (how the passengers for HS2 would have travelled if it wasn’t built) have consistently fallen. With the last set of figures, only 5% of passengers are expected to have shifted from air or car to HS2.

| Classic Rail | New Trips | Air | Car | |

| 2010 economic case | 57% | 27% | 8% | 8% |

| 2011 economic case | 65% | 22% | 6% | 7% |

| 2012 economic case | 65% | 24% | 3% | 8% |

| 2013 economic case | 69% | 26% | 1% | 4% |

2.4 HS2 Isn’t Green

The only mention of HS2 in the 2010 coalition agreement was that it would be part of their ‘vision for a low-carbon economy’. While ministers have claimed HS2 will be ‘broadly carbon neutral’, this omits the carbon cost of constructing the line.

The reality is that because 250mph was plucked out of the air for no real reason, HS2 will use 2-3 times the electricity a ‘normal’ hogh speed rail service would need.

The current official estimate of the electricity HS2 will need stands at 800MW. To put that into context, that’s half the output of one of the reactors planned for Hinkley C, and in more than the total electricity produced by some power stations in the UK.

It is also the case that, to fiddle the figures in the business case, HS2 Ltd have estimated that electricity price inflation will stop around 2035, so for the next 20 years they forecast cost of electricity will go up, and then it will never go up again.

2.5 HS2 – ‘No Business Case’

“So far the Department has made decisions based on fragile numbers, out-of-date data and assumptions which do not reflect real life.” – Public Accounts Committee, September 2013

Normally, for transport projects to get the go ahead, they have to prove that they have a good ‘benefit cost ratio’, i.e. that they will make more money back than they cost to build and run.

With HS2, they have completely fiddled the figures on two massively false assumptions. First, the Government say that all time on trains is wasted, no-one ever does any work on a train. From that, they say that faster journey times have a cash benefit to the economy, quite literally time is money.

The Government then put a cash value on this time, based on the idea that everyone on trains earns massively above average earnings, and they then multiply it by a grossly inflated passenger forecast and this magics up billions of pounds worth of economic benefits.

It is worth knowing that High Speed Rail projects across the world never manage to attract the passenger forecasts which were used to justify building them. Here in the UK, HS1 currently carries about 10 million passengers per year, about a third of what was forecast originally.

Government also have based their figures on HS2 making a profit, despite the fact only two high speed rail lines in the whole world manage that. In Spain, the think tank FEDEA concluded: “None of the high speed lines should have been built and that none has a chance of being profitable.”

2.6 HS2 Not a ‘Magic Wand’ to ‘Transformative the Economy’

Recently, Government have tried to suggest that HS2 will be a magic wand to ‘rebalance the economy’, and that HS2 is ‘essential’ to the ‘Northern Powerhouse’. The problem is that this is that all the experts concur that when high speed rail connects two cities, the economic benefits flow to the dominant city, in this case London.

Looking at the international evidence, there is no question that London will be the greatest beneficiary from HS2. Even when the DfT paid KPMG £250,000 to invent a brand-new, untested methodology to in an attempt to bolster the case for HS2, they also came to this conclusion.

So while HS2 is touted as if it were a magic wand to cure the North-South divide, the reality is it will most likely make it worse. While some Northern council leaders have previously described HS2 as ‘essential’, this is no longer the consensus amongst Northern politicians, academics, and business leaders. Many of them agree that East-West links are more important. If a ‘Northern Powerhouse’ is to be created, most business leaders believe it is the links between those cities which need to be improved. The very last thing which should be done to regenerate the North of England is to make it easier to get to London.

With stations proposed for green belt areas in the East Midlands, Crewe and near Birmingham Airport, development here is likely to mainly consist of residential developments to feed even more commuters into London, rather than genuine regeneration.

In the UK, HS1 has not led to a great deal of regeneration in Kent. A government report on the economic impact of HS1 published in 2015 said that regeneration around the HS1 stations had been limited, that “HS1 has had little impact on underperforming towns” and that along the HS1 corridor, regeneration “effects could not be considered significant to date”.

The perfect example of this is the HS1 station at Ebbsfleet. This connection was supposed to deliver economic development, but as of yet has only delivered a large, under-used car park. In 2015, George Osborne effectively waved the white flag on economic development at Ebbsfleet, stating his intention to build a ‘Garden City’, or more rightly a dormitory town for London commuters, next to the station.

In France, when the TGV was extended to Lille, unemployment in Lille and the surrounding areas jumped relative to the rest of France by about 2%, and has stayed there ever since. The same thing happened in Lyon as many businesses closed their regional offices or moved to Paris.

2.7 HS2 is needed for capacity reasons

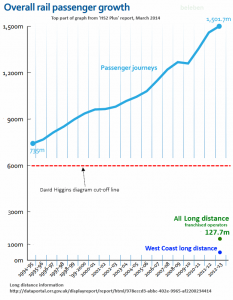

The idea that HS2 is needed for capacity reasons is superficially compelling as everyone who uses trains regularly has been on a busy train. HS2 Ltd point to overall rail growth to illustrate this, despite the fact the vast majority of this is on short journeys, not the inter-city routs HS2 is designed for.

It is true that any new railway will increase capacity, but unlike alternative rail programmes, HS2 would not deliver any incremental gains: it is all or nothing with no additional capacity being delivered until Phase 1 is expected to be completed in 2027. But the reality is that overcrowding is worst on commuter and regional trains and other major rail corridors into London are closer to their capacity limits. The bottom line is that HS2 would deliver capacity where it is least needed at a far higher cost than alternative ways of increasing the number of both seats and trains.

The graph HS2 Ltd like to use about rail growth, with the reality about long-distance journeys added on.

A key assumption of HS2 is that the only way it can ‘free up capacity’ for passenger services and freight is by cancelling existing trains. Once HS2 services are operating between London and Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, traditional intercity services between those cities would be reduced – leaving intermediate stations with a poorer service. Many towns and cities, including Coventry, Stoke-on-Trent, Doncaster, Chesterfield and Wakefield, would have fewer intercity services to London.

The assumed saving from reducing existing rail services, totalling £8.3 billion, is a fundamental part of the HS2 economic case. Yet whenever pressed, iHS2 Ltd claimed rail service patterns would be decided by a future Secretary of State.

‘Britains Busiest Train’ of 2013 from London to Crewe was heralded as the perfect example for why HS2 was needed: however by the time passenger figures had been published in 2014, it was no longer crowded, having been extended from 4 to 8 carriages. Adding more carriages, and reclassifying first-class carriages would add significant capacity across the network

Then the Government argue that there is no room for more trains on the track. In October 2013, the DfT published a supplement to the new strategic case for HS2, making it clear that the case for HS2 now rests on “capacity and connectivity” and that “The West Coast Main Line, on current projections, will be full in the near future”, with a new line needed to provide sufficient capacity for passengers and freight.

This is in spite of the DfT’s own data showing that even in peak hours, most long-distance trains on the West Coast Main Line are barely half-full. They continued, that if a new line is to be built, it should be high speed as that is not an excessive additional cost and it will maximise the potential benefits.

However, since then, London Midland changed their timetable and adding seven trains in peak hours out of Euston in 2014, showing that there was space. Permission was given in 2015 year for new London-Blackpool services and only around half the freight paths on the line are currently used.

The DfT has gone on to undermine their own case, stating that between 7-8pm, just after peak fares end, the West Coast fast lines out of Euston have a current capacity of 15 to 16 trains per hour, despite the fact that during that period there are only 11 or 12 trains using the fast lines.

A capacity analysis from Network Rail goes further than this, demonstrating that Virgin Trains artificially supress capacity on the West Coast Mainline for commercial reasons:

“The entire WCML timetable is effectively dictated by the 20-minute even interval service pattern between London Euston and each of Birmingham New Street and Manchester Piccadilly. This pattern is inherently incompatible with maximum utilisation of key route sections. There is, therefore, effectively a cap below 100% by virtue of this passenger presentation and marketing led timetable structure to maximise revenue.”

Undeterred, in 2015 the DfT said that without HS2, crowding on inter-city West Coast ‘could‘ become particularly acute on Friday evenings between 7-8pm. However, the Autumn 2014 data showed there were only 24 out of 1000 passengers standing on Fridays and 7 out of 1000 on other weekdays, highlighting the fact that capacity out of Euston is hardly the urgent capacity crisis on the rail network.

The reality is that in terms of solving overcrowding, the only likely thing which HS2 might do is solve the commuting problems of Milton Keynes, which could be done by spending £260m on a flyover at Ledburn Junction.

What’s more, HS2 Ltd are assuming that they will be able to run 18 trains per hour in each direction, but evidence to the earlier Transport Select Committee review of HS2 was that nowhere in the world ran 18 trains per hour on a high speed network.

HS2 is presented as the only possible solution to an urgent problem, even though improvements to the existing railway can supply the new capacity that the railway industry say we need. These could be operational long before HS2 opens, and all represent better value for money.

It has also been said that HS2 is needed to increase freight capacity. If space for freight is needed, why build a railway which will not carry freight?

3.0 Inconvenient Truths and Ignored Alternatives

3.1 Better Ways of Improving Rail Services

Spending £56bn on HS2 has a huge opportunity cost, and over recent years other rail projects have been scaled back, cancelled and delayed. With most of these projects also going up in cost the way HS2 has done, it is highly likely that if HS2 which will need about £3bn/year for 20 years, that many other projects will have to be cancelled as HS2 will demand all the money in the transport budget.

Alternatives to HS2 would not cost as much as HS2 and are much better value for money, would benefit far more people, better balanced in meeting needs across the whole country. These alternatives could be implemented much sooner than HS2.

For example, the independent think tank the New Economics Foundation has proposed a £33bn package of investment including major upgrades to the East Coast and West Coast main lines; regional rail enhancements; investment in urban mass transit and bus networks; and improvements to cycling and walking infrastructure. These investments would still leave funds to extend the roll-out of super-fast broadband.

There are also high speed projects, such as HSUK, which have been completely ignored, despite the fact they have lower environmental impacts, more passenger benefits, and lower costs to build and run.

3.2 Speed “Almost Irrelevant”, But Causes Massive Problems

Former Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin has said that for a new north-south railway, the speed was “almost irrelevant” but as HS2 will ‘only’ cost around 9% more than a conventional speed railway, ‘we might as well’ spend the extra taxpayer’s money to make it ultra-high speed. Current Transport Secretary Chris Grayling remarkably said: “One of the myths about high speed two is that it’s about speed”

When proponents say any new railway ‘might as well be high speed’, what they are actually saying is; it might as well not be able to carry freight, it might as well not have any intermediate stations, it might as well not be able to properly interface with the existing railway, it might as well have the greatest environmental impact possible, and it might as well use about three times the electricity as existing high speed railways in the UK and it might as well cost billions of pounds more…..

The design speed affects every decision about the railway. There are a handful of stations on the entire HS2 line (none between London and Birmingham), because they slow the railway down too much. HS2 blasts through sensitive wildlife sites and communities, because the speed means the tracks need to be as straight as possible. Possible connections between HS2 and other railways, such as the East West Railway, have been ignored. Poor connectivity between new HS2 stations and the existing rail network, will result in time lost on onward journeys. Even the DfT say a new high speed line would have higher environmental costs than a conventional speed line.

The economic case for HS2 is reliant on the assumption that time on trains is wasted, so if trains were slower, these invented economic benefits would be smaller. A conventional speed railway, or even a ‘normal’ high speed one, would mean lower cost to build and run, greater connectivity, more freight paths, greater versatility, lower energy requirements, a lower carbon footprint, and would be less damaging to communities and the local environment.

3.3 An Environmental Disaster

“A new high speed line would cost 9% more than a conventional railway and, in certain respects, would have higher environmental costs…” – ‘The strategic case for HS2’, Department for Transport, October 2013 p21

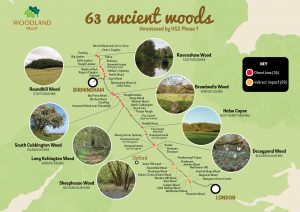

HS2 threatens 350 unique habitats, 98 irreplaceable ancient woods, 30 river corridors, 24 Sites of Special Scientific Interest plus hundreds of other sensitive areas. The ultra-high design speed of 250mph, dictates HS2 tracks have to be as straight as possible, and cannot curve round these important sensitive sites or communities.

When HS1 was built, it led to the establishment of the ‘Kent Principles’, which made environmental and mitigation concerns central to the choice of the route to the Channel Tunnel. As a result, HS1 follows the existing major transport corridors of the M2 and M20 and minimised damage to communities and sensitive sites. Unlike HS2, the top speed of Eurostar trains is 186mph (300kph), with Javelin trains running at 140mph (225kph). For HS2, with the emphasis on ultra-high speed, the Kent Principles have been torn up and completely ignored.

3.4 Ignoring the Real World

The latest HS2 Ltd strategic case document claims

“Despite predictions that new technology would take the place of travel, our demand for both has soared. We’ve seen the launch of Skype, Twitter and faster, smarter tablets and phones, all in just over 15 years. In the same time, rail journeys have doubled to 1.5 billion a year.”

The implication conflicts with detailed studies by Government departments. Overall long-distance travel has been falling, and car usage has been static for the last 15 years, following a period of growth from the 1950s. In contrast, rail usage was static for much of that period, before it began to grow again, after privatisation.

In recent years, owning and running a car has becoming increasingly expensive: The costs of fuel and car insurance have rocketed, pricing younger drivers out of cars. Anti-congestion measures have further discouraged car use in towns and city centres. By ignoring changes on other modes of transports, HS2 Ltd is appearing to encourage a simplistic and one-dimensional view of the interactions between transport and communications technology

It is a deliberate twisting of the argument, and HS2 Ltd have not used any studies to argue for this assertion. Instead they have dotted a few events in internet history on a graph of rail growth from the Office of Rail Regulation, but this assertion that improved technology will increase travel is not borne out by detailed studies by other government departments such as by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. A report produced for them, and published in November 2013 says

“Large corporates have made significant inroads over the last few years into reducing their travel costs (and emissions) by reducing the need for face-to-face meetings through the use of collaboration software and video-conferencing. With affordable faster broadband with low latency now widely available, we anticipate that the next few years will see this trend increasingly applying to smaller businesses.” – p41 UK Broadband Impact Study

3.5 A Railway for the Business Elite

On HS1, not only are the high speed tickets more expensive, but the fares for the conventional speed alternatives have been increasing more than most other fares to try and make HS1 more attractive. The National Audit Office reported that HS1 will cost the taxpayer £10bn more than expected because it has not hit passenger forecasts.

With higher energy and maintenance costs than a normal railway, the only way to keep HS2 fares in line with current services would be a massive increase in taxpayer subsidy for HS2.

Speed-based pricing is already evident on London-Birmingham routes as demonstrated by the price comparisons between Virgin, London Midland and Chiltern, with slower trains being correspondingly cheaper. It is clear that excluding premium pricing in the HS2 model has only been adopted to make the passenger numbers work.

Basically, HS2 will mean putting in a massive subsidy to run something which will only benefit the richest in society.

3.6 An International Disaster

Across the globe, we have seen high speed rail projects are being scaled back across the on financial grounds. Portugal, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands and Belgium have all cancelled planned or existing high speed rail projects. France has even cancelled all new TGV railways not already under construction, with the president of SNCF admitting the focus on the TGV had starved conventional speed railways of funding.

All these arguments against have been known for years

No-one is listening. Is there a hidden agenda that we do not know about

One alternative not mentioned is maglev. UK Ultraspeed proposed a complete system, Glasgow to London AND Heathrow for less than the cost of the present HS2 plan. Since then manufacturing costs have been reduced, installation costs have been reduced, running costs have been reduced and maintenance is one third of HSR.

This needs to be investigated fully as there are other benefits.

Cheaper, faster, greener